Why Aging Makes Your Art Stronger and More Powerful

Becoming your best creative self after you turn 45

My latest public art project went up last week—my first in eight years. Back in 2018, after installing four permanent public art pieces in Denver, I thought, This is it. This is the last project I’ll do. The tight margins, long production schedules, and a newborn made it impossible to continue.

But now, my son turns eight tomorrow, my younger one turns five next month, and last week, I installed another permanent public art piece. I see this as my second act—a post-children comeback of sorts. And for the first time in a long while, I feel ambitious again.

I’m re-posting this article from last year because I found myself rereading it this week—not in celebration of my comeback, but in reflection. Instead of feeling proud, I was dwelling on the time I lost chasing other paths that never brought me the same fulfillment as writing and creating large-scale works. The question on my mind is the very one I pose in the first line of this article.

In a world focused on youth and early achievement, can one still find creative brilliance and success at an older age?

The Evolution of Creativity with Age

While many theories suggest a decline in creativity with age, the extent of this decline varies depending on factors like originality, subject type (arts and humanities versus sciences), motivation, and even gender. However, rather than simply fading, creativity often evolves with age, reflecting shifts in an artist’s priorities and experiences.1

Even if an artist wasn’t a late bloomer, getting older can change how they think about their work, especially when they sense their time is limited.

Researchers studied 1,919 pieces by 172 famous composers to understand how this shift appears in their final works. They found that while these last works may be less original and shorter, they tend to be more popular and artistically significant. This pattern persisted even after considering factors like the composer’s overall productivity and age. As these artists near the end of their lives, their work often becomes simpler yet resonates more deeply.2

Creativity involves thinking of new solutions and creating art; failure is a normal part of the process. Careers in music, acting, and art often come with ambiguity. Aging can increase one's tolerance for life’s challenges, softening the rigid beliefs of youth. With age comes realism—a clearer sense of what works and what doesn’t.

Adaptation and Resilience in Later Life

In his 1987 article ‘Creativity in Aging Persons’,3 Paul W. Pruyser argues that aging can be a creative process accessible to all, not just the exceptionally talented. He identifies the loss of relationships and functional abilities as key aspects of aging that can foster creativity.

For example, older painters who experienced visual impairments adapted by tapping into childhood qualities like playfulness, curiosity, and a desire for pleasure. Edgar Degas, for instance, changed his color palette as he began to lose his sight. These adaptations show how creative individuals can continue to produce meaningful work, offering a model for other older adults facing similar challenges.

Henri Matisse experienced a profound shift in his outlook after surviving major surgery in his early 70s. This near-death experience renewed his sense of purpose, leading him to view his earlier struggles as trivial. Matisse described this transformation as entering a "second life," which brought a fresh, philosophical approach to his art and a revitalized urgency in his creative work. This period led to his famous cut-paper collages.4

Other examples include Verdi, who shifted from composing tragic operas to writing the comedic ‘Falstaff’ in his final years, and architect Philip Johnson, who broke from his modernist roots to design the postmodern Chippendale building. These examples demonstrate how late-life creativity can lead to unexpected and groundbreaking work.5

The Power of Late Bloomers

Late bloomers aren’t just artists who gained recognition later in life—they improved significantly as they aged. Galenson calls these people ‘experimental innovators’ in his book ‘Old Masters and Young Geniuses’.6

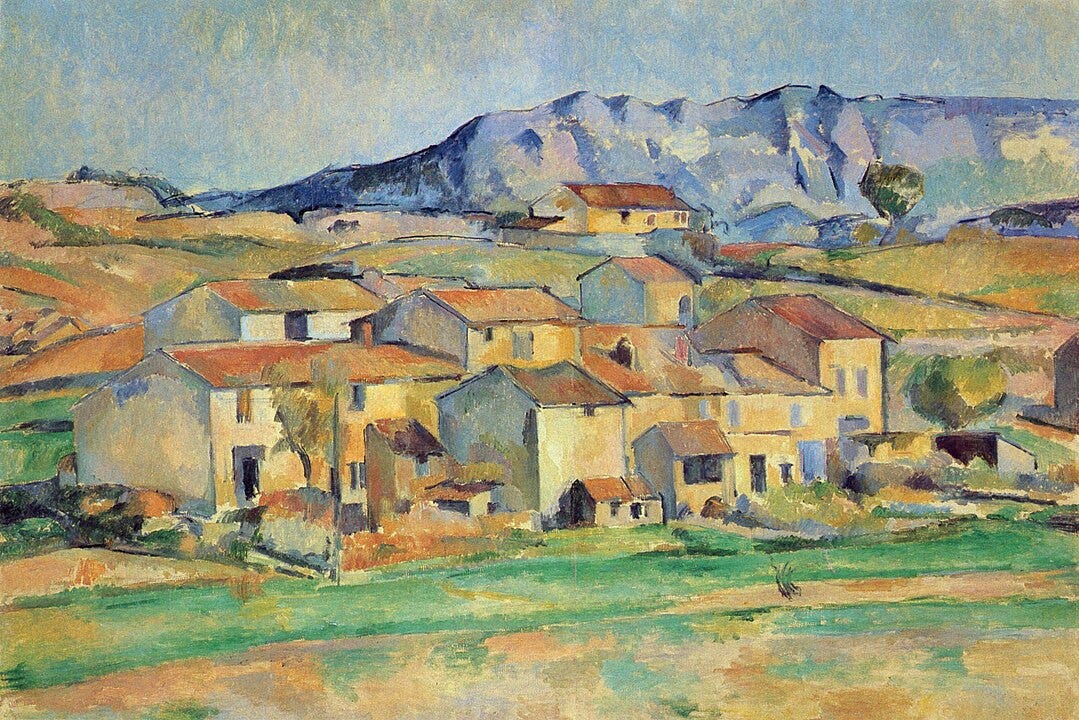

Cezanne, who struggled early in his career, is a prime example. While young Cezanne’s work lacked technical skill, his persistence, and evolution eventually led to his recognition as a master.

Other examples include Morgan Freeman, who gained widespread recognition in his early 50s with his roles in Street Smart and Driving Miss Daisy; Grandma Moses, who began painting at 77, and Samuel Johnson, now regarded as one of the greatest English writers published most of his important work in his forties and fifties, a period of intense creativity that saw the publication of his Dictionary, The Rambler essays, Rasselas, and Lives of the Poets.7

Louise Bourgeois was in her 70s when she gained widespread recognition. Frank Lloyd Wright designed some of his most celebrated buildings in his 80s.

Alfred Hitchcock is another example of late-life creative brilliance. Between the ages of fifty-four and sixty-one, he directed some of his most iconic films, including ‘Dial M for Murder’, ‘Rear Window’, ‘To Catch a Thief’, ‘The Trouble with Harry’, ‘Vertigo’, ‘North by Northwest’, and ‘Psycho’. This period is considered one of the greatest streaks by a director in cinematic history.8

Summing up

Creativity in later life is not merely about holding onto past successes; it’s about transformation and growth. As artists age, they often undergo shifts in their creative processes that reflect the wisdom and experiences they’ve accumulated over the years. This evolution can take many forms. Some may adapt to physical limitations by exploring new mediums or simplifying their techniques, turning what could be seen as a restriction into an opportunity for innovation. Others might find that their priorities shift, leading them to focus on different themes or explore deeper, more introspective subjects.

For example, an artist who once pursued technical perfection might, in later years, embrace a more expressive and abstract style, focusing on conveying emotion rather than detail. A composer might strip away complexity in favor of purity and resonance, creating works that resonate deeply with audiences on an emotional level. This kind of late-life creativity is often marked by a clarity of vision and a sense of urgency, driven by a recognition of limited time and a desire to leave a lasting impact.

In some cases, aging artists even reach new heights, producing work that surpasses their earlier achievements. Their late creations, while perhaps simpler in form, carry a weight and significance that reflects their lifetime of learning and growth.

This late-career creativity often resonates with audiences in a unique way, offering profound insights into the human experience and showcasing the enduring power of artistic expression at any age.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2714866/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2803611/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3676539/

https://www.ft.com/content/59192b0c-b994-11e3-b74f-00144feabdc0

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2695166/

https://bookshop.org/p/books/old-masters-and-young-geniuses-the-two-life-cycles-of-artistic-creativity-david-w-galenson/8910986?ean=9780691133805

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/06/successs-late-bloomers-motivation/678798/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/10/20/late-bloomers-malcolm-gladwell?intcid=mod-most-popular

Thanks for the thoughtful piece and great to hear about your public work.

I wonder why this article is written through the lens of male Art history especially since the writer is a mother and an artist?

The experience of women is different than that of men. Women need to balance things in ways that vary from men. Sometimes women do not get recognition until late in life or not at all. Whereas their male counterparts often do not face the obstacles of invisibility. In a biography of Louise Nevelson, she said it was “too little too late.”

I appreciate reading this! I’m in my late 40’s and decided to jump into some new creative endeavors in 2025. Motivation fuel is always helpful!