Clement Greenberg, an influential American art critic, was a leading proponent of Abstract Expressionism. His belief was that art should push boundaries and innovate. He championed the avant-garde movement and rejected the traditional, naturalistic depictions of beauty as "kitsch,"1 advocating instead for modern and abstract forms as representative of "good art." In Greenberg's view, artists working within these innovative frameworks were inherently "good artists."

For Greenberg, Jackson Pollock's Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950—an iconic Abstract Expressionist work—epitomized good art. It represented a break from tradition, a bold exploration of new visual languages2.

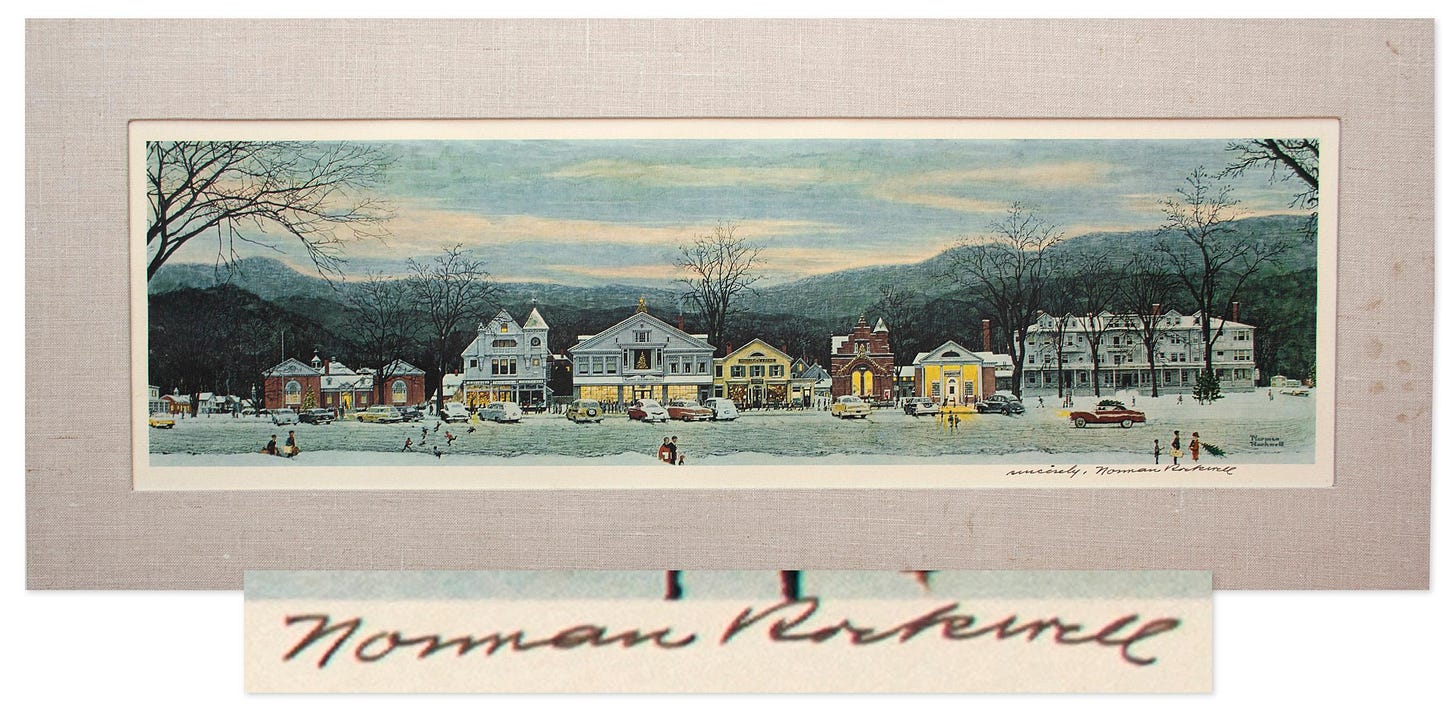

In contrast, Greenberg viewed Norman Rockwell’s ‘Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas’ as kitsch for its adherence to familiar, representational aesthetics, which he saw as commercial and lacking in critical depth.

However, the idea of what constitutes a "good" artist is not solely based on inherent talent or some divine gift. Rather, it is shaped by the arbitrary rules and preferences of those in positions of cultural privilege and power. These gatekeepers influence broader artistic tastes, determining what gets shown in museums and sold in galleries as "good art."

This subjectivity is particularly evident in the words of art critic Roberta Smith3, who reviewed a Pre-Raphaelite exhibition at the National Academy of Art. In her New York Times review, she writes:

"You won’t see much in the way of great paintings, but you will probably have a great — which is to say, entertaining and edifying — time. Perhaps inadvertently this show usefully parses the difference between quality and influence, reveals much about visual culture today, and even provides a yardstick by which to gauge your own sophistication."

Smith's words reflect how the art world often equates personal taste with intellectual sophistication. While some audiences may use such exhibitions to measure their artistic sophistication, this is a subjective process. Artistic value is not a fixed metric, and what is deemed "good" art varies according to personal, cultural, and institutional standards.

Historically, art influences art. Even Vincent van Gogh borrowed heavily from earlier artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-François Millet, and Rembrandt (Homburg, 1996). This illustrates how artistic styles often evolve within established traditions.

But does this mean that only those in privileged positions decide what art gets sold or displayed? While certain gatekeepers wield influence, art's value is not determined solely by the powerful. There are many reasons art can be considered "good."

Good art pushes boundaries and challenges tradition, as avant-garde and modernist movements did with realism.

It can evoke a wide range of emotions—joy, sorrow, awe, or grief—whether through a deeply personal piece like a portrait of a beloved pet or the grandeur of a vast landscape.

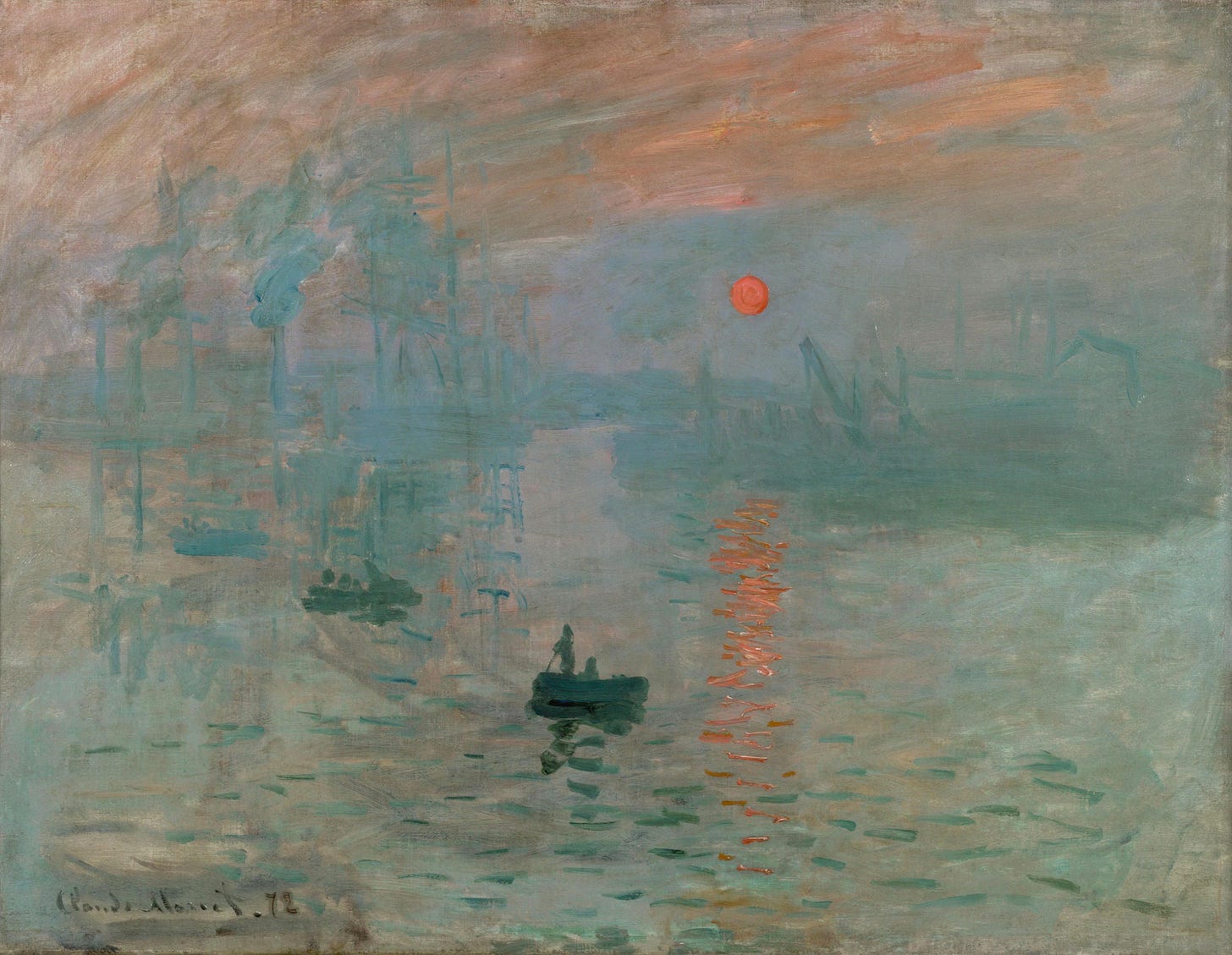

Art communicates the cultural and social trends of its time, like the rise of Impressionism in the late 19th century, a movement that continues to dominate the art market.

Aesthetically, "good" art can be rooted in the beauty of its time, such as the classical influences in ancient Greek or Roman art. It can also challenge our perceptions, as seen in the fragmented perspectives of Cubism or the dreamlike narratives of Surrealism.

Some works, like Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, captivate viewers through mystery and storytelling.

Context further shapes art's value. Art schools teach students how their work fits within the broader canon of art history.

Critics play a role by making value judgments that shape what is included in museums and, by extension, the tastes of the art market, including galleries.

Commercial art is driven by demand and branding, as seen in collaborations with high-end brands like Nike and Uniqlo, with artists like KAWS and Takashi Murakami making waves in this space.

Meanwhile, more traditional or abstract works, whether in oil, acrylic, or digital mediums, find markets online, through platforms like Etsy, and in local stores. These self-taught artists bypass the gallery system but still create art that resonates with audiences.

Ultimately, art is experienced differently by each person. For an art critic, it might offer intellectual stimulation. For an office worker, an impressionist landscape in a windowless cubicle could provide emotional escape. A skateboarder might feel a sense of belonging wearing Nikes adorned with street art. A mural in a neighborhood might inspire social change. In all these cases, the art is "good" because it serves a purpose.

In conclusion, the value of art lies not in rigid definitions of "good" or "bad," but in its ability to evoke something meaningful in the viewer. Whether it is intellectual stimulation, an emotional response, or a moment of introspection, art's true power comes from its capacity to connect with people on different levels.

An artist's success is not solely based on technique or adherence to tradition, but rather on their ability to communicate through their work—be it through joy, sorrow, beauty, or disruption.

Ultimately, art’s significance is subjective and dynamic, changing with each viewer, context, and moment in time. An artist’s ability to make this connection is what elevates their work, ensuring it transcends the boundaries of medium and tradition to leave a lasting impact. In this way, art becomes a mirror for both the artist and the audience, reflecting not just the world, but our individual experiences and emotions.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_Greenberg#%22Avant-Garde_and_Kitsch%22

https://www.youtube.com/@crashcourse

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/29/arts/design/pre-raphaelites-at-national-gallery-of-art.html