Before we dive in, a quick update: I will no longer be posting “new opportunities” in this newsletter. This is to streamline my focus toward exploring alternative economies in the arts—the systems, structures, and models that can help artists build stability, autonomy, and ownership over their work. For future opportunities, I recommend using the excellent Artist Opportunity Database by Fractured Atlas.

I’ve been wrestling with this article for the past week. There’s no shortage of papers and reports on alternative economies for the arts—most produced by organizations that have secured funding and then used it as discretionary capital to test ideas in guaranteed income (GI), solidarity economies, or other social experiments.

At its core, this article scratches the surface of economic models—emerging, experimental, and proven—that can give artists lasting stability, autonomy, and ownership over their work.

This research is also the seed for an upcoming e-book on alternative artist economies—how they work, how artists can participate, and how they might be expanded. The book will weave together my past articles (both paid and free) with new research and interviews. I’ll release some chapters here as standalone articles. Paid subscribers will receive the full e-book for free when it’s published; for everyone else, I’ll share a pre-order link at a discounted rate.

A New Legal Structure: The Artist Corporation

This past week’s notes began with Yancey Strickler’s TED talk on a new legal structure for creative work. Strickler—co-founder of Kickstarter, founder of Metalabel, and an artist himself—proposes what he calls an Artist Corporation1 (A-Corp). While it doesn’t yet exist in law, the concept is designed to treat artists as full economic actors.

The push for an A-Corp came from a practical problem. A collaborative book project on Metalabel made $70,000, with a new cooperative writing project projected to hit six figures. Incorporating the venture revealed that no existing structure met their needs—especially for equitably splitting revenue among multiple creators. They aim to push for legislation by 2026.

While my focus here isn’t the A-Corp itself, it’s a useful entry point into a broader conversation: how new models—impact investing, solidarity economies, cooperative platforms—can give artists greater stability and ownership, much like how the B-Corp model created a space for mission-driven businesses between nonprofit and for-profit.

Impact Investing in the Arts

Art philanthropy has long been a backbone of institutional funding. Impact investing in the arts, however, is still relatively new and often highly amorphous. Financial returns tend to be minimal, yet some investors see value in directing capital toward long-term infrastructure—such as artist-led land trusts like Artspace—that secure space and resources for creative work over decades. I’ve been toying with the idea of raising a small fund to do something similar.

An example is Mary Stuart Masterson, actress and filmmaker, who moved from NYC to the Hudson Valley to raise her family. Turning down a TV role in Vancouver to stay close to home, she decided to bring the work to her.

By advocating for tax incentives, adding film-related degree tracks at local colleges, and attracting investment in production facilities, she helped transform the region into a media hub.

In 2016, Masterson launched Stockade Works2, a nonprofit training local residents for film and TV jobs, grounded in diversity, equity, and inclusion. Her startup arm, Upriver3, closed last year.

As she wrote in the Creativity and Arts Report for Cornerstone Capital Group:

“The future I am building can’t be built with philanthropy. It has to be built with investment capital that shares the values of diversity, equity and inclusion… Investors who, like me, are radical optimists.”

On a broader scale, organizations like Upstart Co-Lab4 are pioneering the impact investment ecosystem within the creative economy. Founded to catalyze and scale investment capital for creative enterprises, Upstart Co-Lab partners with fund managers, philanthropists, and community leaders to build a $100 million portfolio dedicated to creative economy funds and companies. Their mission is to unlock financial flows that have historically bypassed artists and cultural entrepreneurs, especially those from underrepresented communities—more on them in future articles.

Solidarity Economy

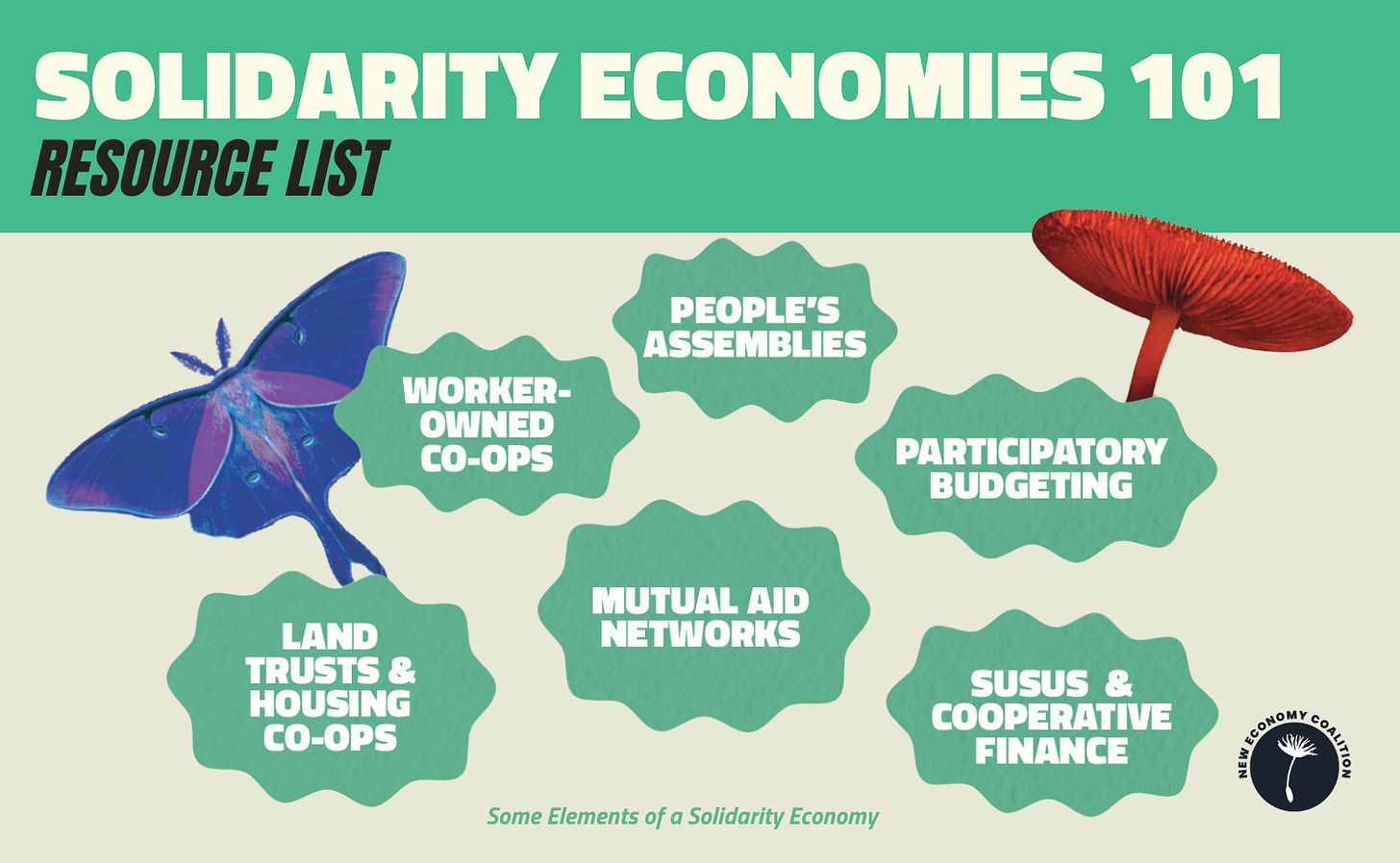

Like impact investing, solidarity economies prioritize community well-being over pure profit. But they differ in one key way: they are participatory and collectively governed.

At its heart, the solidarity economy is about building systems where everyone involved has a stake and a voice. It encourages collective ownership and shared decision-making, ensuring that benefits are distributed fairly and equitably among members.

For artists, this model can take many forms:

Artist cooperatives where creators pool resources, share studio space, and split profits democratically.

Media collectives that produce and distribute work collaboratively, without the influence of commercial pressures.

Open source art and technology projects that make creative tools and content freely available and collectively maintained.

Platform cooperatives—digital platforms owned and governed by the artists themselves rather than by outside investors or corporations.

A strong example is Stocksy United, a stock photo co-op where members earn 50–75% of licensing fees and share surplus revenue annually. Every member co-owns the platform and has an equal vote.

Yet after combing through institutional websites, I found many solidarity economy initiatives heavy on theory5 and activism but lighter on tangible, scalable outcomes.

Most artists—like other workers—want to make their work and have a reliable safety net: autonomy, ownership, and steady income. Too many funding frameworks overlook these basic needs, focusing instead on short-term programs rather than long-term stability. I will break this down further with examples in my future articles.

Universal Income

The Creatives Rebuild New York (CRNY)6 initiative is one of the most ambitious artist GI experiments. With a $125M budget, CRNY provided $1,000 per month to 2,400 artists for 18 months. The results were striking: more time for creative practice, stronger family connections, better mental and physical health, and greater food security.

This model challenges the persistent precarity in the arts—where unpredictable income streams, lack of benefits, and gig-based work dominate. By decoupling artists’ basic survival from project-based funding or sales, guaranteed income creates a baseline that allows creativity to flourish without the constant pressure of economic uncertainty.

Similarly, the Artist Employment Program (AEP)7 provided steady jobs for artists, showing that stable income leads to better art, stronger communities, and improved livelihoods. But when the program ended, many participants returned to precarious gig work—highlighting that lasting change requires systemic shifts: stable jobs, fair pay, benefits, and protections.

The program highlighted the urgent need for structural changes in the art world and broader economy—such as expanding stable job opportunities, ensuring fair pay, and providing benefits like health insurance and retirement plans. Only then can artists escape the cycle of instability that stifles creative potential.

Artist-led Platforms

Some solutions are emerging from education and skill-sharing.

VAWAA8 (Vacation With An Artist) connects artists with learners worldwide for apprenticeship-based workshops.

Unlike platforms that primarily rely on online visibility, likes, or follower counts, VAWAA prioritizes the transfer of craft, technique, and creative philosophy. Artists offer workshops and residencies in diverse disciplines such as felting, quiltmaking, indigo dyeing, bookbinding, and more—skills often marginalized by the fast-paced, trend-driven nature of contemporary art markets.

VAWAA’s approach suggests a broader possibility for artist-led platforms—ones that are artist-owned and governed, where control and revenue remain with the creators rather than corporate intermediaries. Imagine if platforms like VAWAA, Etsy, Patreon, or Bandcamp operated as cooperatives, distributing profits equitably and empowering artists to shape their economies collectively.

Closing Thought

The global creative economy is valued at $2.2 trillion. As Jelena Trkulja, senior adviser for Qatar Museums, notes9:

“Some countries are realizing that cultural industries should be deeply embedded in government strategy for social, economic, and human development… because the returns are there.”

The real question: will we design economic structures that truly serve artists—not just in theory, but in practice?

The challenge—and the opportunity—is to create economic structures that are flexible enough to meet artists where they are, yet durable enough to support them for decades. This means borrowing from multiple models: the investment discipline of impact capital, the shared governance of solidarity economies, the accessibility of platform-based income streams, and the baseline security of guaranteed income.

Thank you SO MUCH for taking the time to cultivate and compile these ideas, and for making them available for free. Most people don't quite realize how important and relevant these concepts are today- especially with the rise of AI and shifting values about what constitutes "the good life". The cultural landscape is changing, and you are addressinh big problems that haven't fully emerged. But they will. So impressed and grateful to have discovered your work.

I’m so glad this post came across my feed. I’m curious to hear more on a large variety of these topics, so I’m going to subscribe and hope you keep writing about it. For now, my main questions are:

1. How did the New York program manage to raise $125M? Who were the investors and what, if any, were the stipulations? What did they do with the remaining money?

2. What, specifically, differentiates impact investing from other forms of investing, and if the expected returns are small, how does one persuade others to provide investment capital?

3. What do you view as the ideal structure, or combination of these approaches?

I’d be genuinely interested in seeing a deep dive on all of these different options, and also interested in following along.