Kaws and the rise of Artepreneur

From a street tagger to one of the most powerful and expensive artists in the world

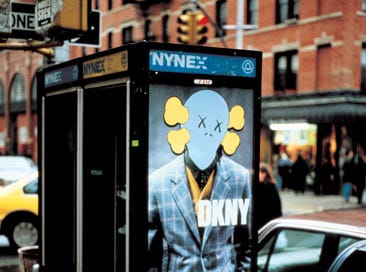

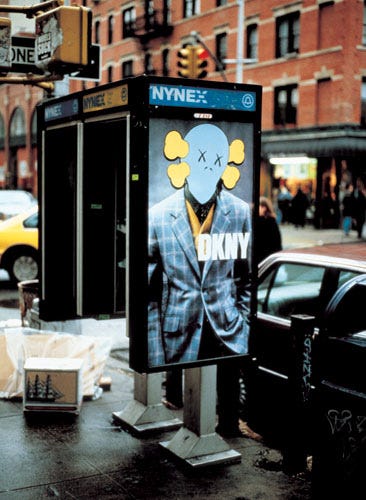

Kaws is a made-up name for the former street artist and now fine artist Brian Donnelly. He is an American graffiti artist and designer whose work spans different media, including sculptures, prints, limited-edition toys, clothing, and more. In the 1990s, he started subtervising bus shelters, phone booths, and billboards in NYC using his cartoon figurative characters, like Companion and Chum, with X-ed-out eyes.

Kaws has gone from being a tagger to being one of the most expensive artists in the world, with considerable influence and following. He has been a successful artist for most of his career, starting in the early 2000s, but his recent growth has been exponential. We will mainly cover his early career and entry into the fine art world.

Self-Subsistence

One of the leading obstacles artists face is not having time to work on their art because of financial needs like rent.

KAWS has never relied on the traditional art world for success. His work has a stable consumer base and appears bold and straightforward. It operates free from the limits that the conventional art world may impose on artists, creating a broader and more enduring presence in both art and culture. This excerpt from his interview for Paper magazine hit a chord with me.

"For me it's about cross-pollinating, it's that chance to bring kids who follow me into museums. When I was a kid my first introduction to art came through graffiti, skateboarding and the Pop Shop," KAWS recalls. "I remember the way Keith Haring's art made me feel comfortable walking into a gallery or a museum. I just want to make stuff that no one is ever too stupid to get."

While most artists are not looking to ‘make stuff that no one is ever too stupid to get,’ there is a valuable lesson here. Having a segment of your work with a broader appeal can help you support more ambitious work and even create a market for it, which is what Kaws did.

Finding a niche: Japanese collectibles and streetwear culture

Kaws was lucky enough to find his artistic cluster. It all started when Japanese designer and music producer Nigo met Kaws in 1996 and became a patron. He collaborated with Kaws on many earlier works, including the 2005 painting ‘The Kaws Album.’ which sold at a record price of $14.7 Million at Sotheby’s in 2019.

Visiting Japan in the late 90s, Kaws was inspired by the Otaku subculture and its obsession with toys and collectibles. Japan has a massive streetwear culture, and the hype brands include Bape, Supreme, and Yeezy, all of whom Kaws has worked with since his early years.

In 1999, Kaws had the chance to design and produce limited-edition vinyl toys for a cult toy and streetwear company called Bounty Hunter in Japan, which sold out immediately.

Kaws' initial success with the Bounty Hunter series marked a pivotal moment, establishing his ties to Japan's streetwear culture. His collaboration with Medicom Toy, renowned for their Kubrick and Be@rbrick collectibles, was particularly significant. This partnership eventually led to the creation of OriginalFake—Kaws’ brand that seamlessly combined art, toys, and streetwear.

What started as a niche project became a key element of his global impact, uniting collectible design and contemporary art.1

His first toy, COMPANION, is a dystopian Mickey Mouse with a skull and crossbones for a head and crosses for eyes. It is a 3D version of the figures he drew on the billboards and later blew up into inflatables and giant public art pieces.

A Cult Following

The earliest mentions of Kaws on Google were on Hypebeast. Hypebeast, at least in its early days, was a place to sell new products and design collaborations with underground streetwear brands with a loyal cultish following. Kaws and other street artists like Stash and Futura played a big part in this scene. Young collectors now view Hypebeast as the bible of art and style2 and Kaws as a poster child.

Kaws also sold his toys and T-shirts online as early as 2002, before the advent of social media, thereby taking ownership of his distribution.

Here is a quote from Kaws highlighting his need to get his work out in any form or format.

‘When I was doing graffiti, my whole thought was, “I just want to exist.” I want to exist with this visual language in the world… It meant nothing to me to make paintings if I wasn’t reaching people.’

Kaws has to work hard at many things, but not on his subject matter. He works with widely appealing subjects such as American pop culture and cartoons.

He also paints over brands like Calvin Klein, Marlboro, Guess, and others. According to Greg Allen, an art blogger, brands are familiar, and consumers like brands for the sense of comfort that familiarity brings. Brands appeal to a large audience and can help an artist develop mass appeal, like the works of Andy Warhol or Jeff Koons.

Like brands bring about familiarity, cartoons tap into nostalgia and childhood memories, according to Alan Zeng, the founder of Paddle8's Street Art department. This reappropriation of familiar and mainstream culture has gathered Kaws a cult following.3

Social media caught on with Kaws’ cultish following. He has 4.4M Instagram followers and more hashtags than Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst combined, probably the most significant following of any visual artist.

The long lines outside streetwear clothing stores have given way to lines outside museums. This "artification" of mass culture has turned Kaws consumer goods into gallery-worthy art.

He has orchestrated much of this by controlling his collaborations and distribution and being an early adopter of technology.

Riding the wave of the Changing Art Scene

Unlike most artists, Kaws didn’t begin his career in a gallery. Instead, he recognized the advantages of showcasing his work on the streets and mass-producing pieces to grow his audience. This strategy was so successful that it eventually caught the attention of collectors and critics.

As Gen Z is reshaping the art market, the traditional art world, eager to stay relevant, is adapting by embracing accessibility and appealing to a broader, younger audience. This shift is marked by collaborations with pop culture icons, digital engagement, and the inclusion of artists like Kaws, whose work bridges the gap between fine art and mass appeal.

Here is an excerpt in the NY Times about his rise, which is very apt:

Donnelly (Kaws) and Companion hadn’t changed much since their tagger days, but the world around them did. If the art market used to ardently avoid all things commercial and recognizable as anathema to its basic power structures, the industry was now unapologetically chasing after them. It no longer mattered that Donnelly was popular with hypebeasts and children. If there was profit to be made, it wasn’t just that the old rules didn’t apply; there weren’t any rules at all.4

Kaws Artistic Cluster

Kaws's active engagement with the artist community, from promoting others' shows to collecting their work, paints a heartwarming picture of camaraderie in the contemporary art world. His visits to spaces like Taka Ishii Gallery evoke a modern-day version of the Impressionist gatherings—collaborative, inspiring, and deeply supportive. While the café culture of the past is now replaced by Sapporos and social media, the essence remains: artists uplifting each other and shaping the cultural landscape together.

It took Kaws over a decade of regularly showing and participating in his art cluster to get a solo show at a well-known museum—the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art—in 2010. He worked for it, taking the stair-step approach, slowly building the fine arts side of his career by collaborating with cross-pollinators like Takashi Murakami and others.

For Kaws, art wasn’t a side hustle—it was his full-time identity, marked by unwavering commitment and the ability to show up as both an artist, a collaborator, and a friend.

A Businessman and an Artist

One critic compared Kaws collectibles to a happy meal at McDonalds, where the collectibles were the toy used to sell the meal, in this case Kaws art. Even though this is meant as a disparagement, it is an appropriate metaphor for how Kaws’s business has spawned.

Usually, artists create prints and editions related to full-scale artworks. Kaws reversed this order of operations. He started selling his toys first and then graduated to galleries. It is quintessentially ‘Entry through the Gift Shop’.

Kaws has always been very selective about his brand and where he exhibits his work. He didn’t have a gallery until much later in his career when he was already an established designer and artist. He did, however, have a store called Originalfake that he opened in 2006 to sell his toys and streetwear line.

Kaws sold his work through this store and experimented with sculpture. He developed a loyal base of collectors that included famous streetwear designers and hip-hop artists like Kanye West and Will Pharell. He did album covers for both of them and a jacket for Jay-Z in collaboration with Nigo in 2005.

Here is what he had to say about other (more talented) graffiti artists who came before him:

“Well, I learned to be guarded with where I exhibited my stuff. I grew up under Futura and Dondi White; CRASH was one of my best friends. They were all glamorized during the ’80s in the art scene, and then it dropped them. [The art] is kind of like a kid, or like letting someone watch your pet: You want to be careful with where it winds up”.5

Kaws has been careful and lucky. He has come of age in the art world, where mass media rules and museum elitism feel old, tired, and out of touch. Kaws's work is seen as democratic and accessible, whether it is a million-dollar painting or a $10 toy.

YouTube is full of Kaws's unboxing videos. While this may be common for iPhones, it is not common for a visual artist.

According to Kaws, being accessible is part of the point.

“When I was younger, I wasn’t going to galleries, I wasn’t going to museums … There was a lot of ‘this is fine art’ or ‘this is not fine art’; ‘this is commercial’, ‘this is high art’. In my mind I thought, art’s purpose is to communicate and reach people. Whichever outlet that’s being done through is the right one.”6

But is his Art good?

Kaws' work has sparked criticism, especially within the fine art world. Many articles about him either recount his rise or harshly critique his work, dismissing it as unworthy of attention.

While it’s unclear if this controversy has fueled his mythic status, it has undoubtedly sparked essential conversations about the nature of art itself. To me, this is the proper role of art: to provoke dialogue. Kaws’s work does just that—it elicits strong reactions, from excitement to anger.

Art Newspaper published a thorough critique that delved into the meanings behind his work, further contributing to the ongoing debate about contemporary art. While Kaws's art may seem superficial to some, it challenges traditional concepts and inspires meaningful discourse about the current state of the art world.7

https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/originalfake-kaws-streetwear/#:~:text=While%20he%20was%20thrilled%20with,OriginalFake%20was%20born%20in%202006.

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-6-standout-artists-prospect-new-orleans-triennial-2024

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/kaws-what-party-brooklyn-museum-1948026

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/09/magazine/the-surprising-ascent-of-kaws.html

https://www.complex.com/pop-culture/a/complex/kaws

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/sep/19/kaws-artist-exhibitons-melbourne-london-brooklyn

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/kaws-democratized-art-peddles-relatable-motifs-exhaustion-death-63649/

Fascinating. Thank you for your deep dive and opening new worlds for me.