How Fernando Botero Defied Critics and Won the World

Lessons from Botero’s Career

Last week, I wrote an article, ' The Authenticity Advantage,’ discussing how authenticity could be subjective. Another Substack writer pointed out that the concept of authenticity often operates within the boundaries set by institutional gatekeepers and society. The ‘art world’ tends to privilege certain voices and ideas that align with the established narrative.

I agree with this fellow Substack writer. Authentic art often thrives outside the mainstream ‘art industry.’ It is difficult to be authentic while conforming to the art world's definition of art. On that note, today, I’m writing about Fernando Botero, who came from humble beginnings, stayed true to his vision, ignored the critics, and became one of the most renowned and commercially successful artists of his time, entirely on his own terms. Here is a compelling excerpt from an interview he did with Artforum.1

“I don’t know. I just make paintings and sculptures the way I like. I have to be the one taken by my work. Some people say to artists that they should change. Change what? It’s like saying, why don’t you walk differently or talk differently. I can’t change my voice. That’s the way I am. I work every day because I have never found anything that gives me more pleasure than painting.”

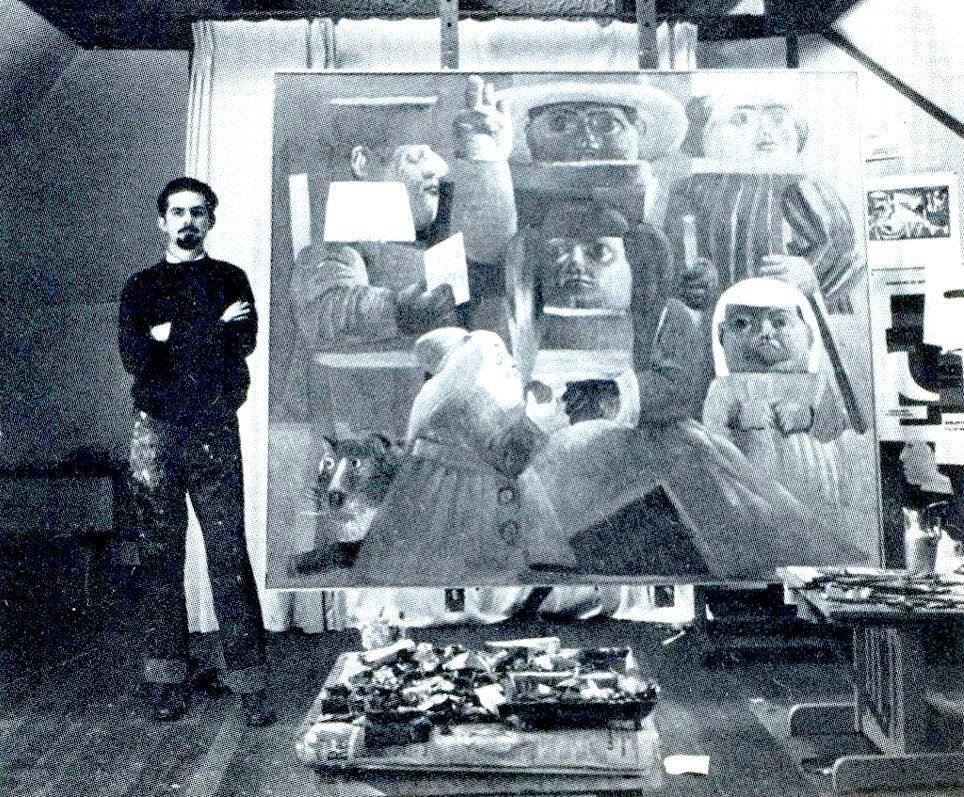

Fernando Botero grew up in Medellín, Colombia, the son of a traveling salesman and a seamstress. His father passed away when Botero was young, leaving his family impoverished. His mother worked as a seamstress to raise him and his two brothers. Fast-forward to today: Botero is one of the most commercially successful and wealthiest artists of his time. His signature style—featuring rotund, exaggerated figures in various settings—has earned widespread recognition, with his pieces commanding prices between one million and five million dollars at auction.

His story is a true rags-to-riches journey. But how did Botero make this incredible leap? Some might say it was luck—and yes, luck did play a role—but not the kind of blind luck where success is entirely out of one’s control. Instead, his success was tied to the kind of luck that comes from being active, persistent, and ready to seize opportunities when they arise.2

Singular vision and growth

Most of us meander through life and find our calling much later. Botero seemed to have his mind set on painting from a very early age. He remembers telling his mother about wanting to be a painter and her saying, “Fine, but you’re going to die of hunger.” However, she never stopped him from doing what he wanted with his life.

Growing up in Medellin, Botero was influenced by the Baroque style of colonial churches and city life. When his uncle enrolled him in a school for matadors, he began drawing bullfighting scenes.

At age 16, he had a group show in Medellín and, at age 19, a solo show at the Leo Matiz Gallery in Bogotá. Meanwhile, he supported himself as an illustrator for a literary magazine.

Botero always wondered why being an artist had such a strong pull on him. He remembers the sheer elation he felt when he was in the presence of great art. He zeroed in on it and got to work. Botero wasn’t exposed to any art museums or cultural institutions growing up. He mostly derived the inspiration from his life and surroundings. In an interview with Artforum, Botero once said, referring to his Colombian roots,3

“If you are from a Third World country you have to find your feeling of universality. It’s not a gift you have when you are born.”

He had intrinsic motivation and a hunger for knowledge. He was also very adept at making enough money to pay for the next adventure in his life. At age 20, he won second prize in Bogotá's Salón Nacional de Artistas. He used the money to travel to Barcelona, Madrid, Paris, and, finally, Florence, where he copied the work of masters like Francisco de Goya and Diego Velázquez, drawing inspiration from the works of the Early Renaissance masters.

This exposure allowed him to formally understand the art canon as it existed in Europe, which inspired his figurative art and penchant for volumetric shapes. He had an ' aha ' moment when he returned to Colombia (where he got married) and then Mexico. Here is what he said about this moment in his interview with Artforum4 and how it laid the foundation for the next 70 years of his life.

“One day I was drawing a mandolin, and I was going to make the hole in the middle of it. I did one little hole that was not in relation to the size of the instrument and to my surprise I saw that now the mandolin had two monumental dimensions—volume and scale. There was something exciting about the dynamic of plasticity in these wild proportions.”

Just enough money

While reading articles and interviews about Botero, I noticed a consistent theme: he always ensured he had enough saved for his next adventure. His jobs and accolades often serve as stepping stones rather than endpoints, as Botero frequently moves to a new city or country, creating fresh opportunities for himself wherever he goes.

When he was 16, Botero participated in a group exhibition with other Colombian artists and had his illustrations published in El Colombiano, one of the major newspapers in Medellín. He used cash to pay his tuition fees at the Liceo de Marinilla de Antioquia High School. 5

At 19 (or 20), Botero won a $7,000 national art prize in Colombia and went to Europe. Here is a quote from his interview with the ART News.6

“I was living in Madrid on a dollar a day; that’s what my room and three meals a day cost me. I was in Europe for nearly three years on the $7,000.”

When Botero first came to New York in 1960, he had just enough for rent.

“I had $200 in my pocket, I couldn’t get a gallery. There was a gallery near the Museum of Modern Art. One day, the dealer came to my studio. A lot of my drawings were on the table. He said, ‘I’ll give you ten dollars a drawing.’ We started counting. There were 70 drawings, so he paid me $700. It was a fortune for me at the time.”

Ensuring he had enough savings to support himself for a set period allowed Botero to focus on his art without interruption, enabling him to continue creating work and pursuing his vision.

Being Authentic and Recognizable

All great art comes from the unique identities of the artists. Here is an excerpt from a New York Times interview with Botero.7

“I believe that if you want to be universal, you first have to be parochial, and belong to a specific land….The art of Goya belongs to Spain, and the art of Monet belongs to France. These artists achieved universality by representing their own worlds, and by tapping into their roots, they tapped into the deepest fibers of commonality that we all share.”

Botero’s art combined Latin influences, such as colonial art in Medellin, pre-Colombian art, Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo’s work, and rural Colombia alongside European masters. The most unique nature of his work is his voluminous figures in Latin American streets, as satirical portraits, mundane household settings, political occurrences, and figures, all mixed with wit and satire. His work is instantly recognizable and feels accessible. It’s regional and universal at the same time.

You only need one

After spending a few years in Colombia, Botero moved to New York City and settled in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood buzzing with creativity. He lived in a building where many other artists also lived and worked. One day, Dorothy Miller, a curator for MoMA, visited another artist in the building for a studio visit. During her visit, she stopped by Botero’s studio for a quick look and acquired one of his paintings for the MoMA collection.

That one incident, which can be attributed to being at the right place at the right time, opened Botero’s career up and got him noticed by the who’s who of the art world, including Claude Bernard in Paris, the Marlborough Gallery in New York and Ernst Beyeler’s gallery in Basel.

Playing a different game

In the 1960s, when Abstract and Pop Art were all the rage, especially in NYC, Botero’s work seemed misaligned and out of tune with the trends. However, Botero’s debut exhibition with Marlborough Gallery sold out, starting a decades-long partnership with the gallery. Here is an interesting story that Botero tells of artists of that time.8

“…. I invited a group of artists I’d met at the Cedar Bar to come and see my work. One of them brought his son, who was four or five. As I took out my work the man would point to the paintings and say in an infantilizing voice, “a-p-p-l-e, p-e-a-r,” to the child. He said absolutely nothing to me.”

I don't know where the above artist is right now, but he probably doesn’t have a museum named after him.

I found many parallels between Botero and Kaws. Although both have had shows in numerous museums (Botero has his own museum), their work spans outside salons, academia, and so-called formal art institutions, connecting directly with the audience.

To sum it up

Here is some advice from Fernando Botero for the younger generation of artists.9

“An artist is born like a priest is born. If they are born an artist, I would tell them art is not a game, it is something very serious which completely requires everything you have to give.”

Fernando Botero’s life and work underscore a crucial point: authenticity isn’t just about creating art—it’s about living a life true to your values and vision, regardless of external pressures. Botero didn’t play by the rules; he played his own game. In doing so, he found personal fulfillment and reshaped what it means to be a successful artist.

A fascinating piece. It seems to go against some of the ideas of your previous piece, but the common factors of consistency and dedication to a particular vision remain.