Don’t Just Survive—Build Equity As An Artist

Betting on yourself and inspiring others to do the same

This piece explores how alternate economic models—like universal basic income, demand-side subsidies, and fractional equity—could reshape how artists are supported.

Can Universal Income and Direct Subsidies Work?

I just read a paper1 on cultural subsidies that got me thinking. It discussed how direct financial support for artists—such as grants or stipends—can sometimes oversupply the market with more art without increasing the number of buyers. This creates a situation where there is more supply than demand, forcing artists to lower their prices to sell.

The author suggests that instead of focusing solely on direct support, we should invest in indirect subsidies2—such as making museum tickets more affordable, strengthening art programs in schools and colleges, and finding ways to bring more people into the world of art as viewers, participants, and future collectors. That way, we grow the audience and appreciation for art, which could help artists make a living in the long run.

While I see the point, I don’t think it’s an either/or. We need both. Currently, it seems that the art world is often sustained by those who have financial safety nets—such as supportive parents or partners—which allows them the time to build their careers. But what about the talented artists who don’t have that kind of backing? Without some form of direct support, they’re more likely to burn out before reaching key moments in their practice.

A balanced approach to subsidies could help level the playing field and maintain a more equitable ecosystem.

Fractioequity means an artist retains a share in the future value of their artwork—even after it is sold. Instead of being paid only once, the artist benefits each time the work changes hands or increases in value.

If universal income imagines a world where all artists have basic support, fractional equity imagines a world where their success can be shared—by the artist and their supporters.

One is structural safety; the other, opportunity. But public support isn't the only way to reimagine artist economies. In parallel, the private market has started experimenting with models that treat artists more like entrepreneurs—and collectors more like investors.”

So what’s the deal—does universal basic income hurt artists, or does it help them? And are demand-side subsidies a better alternative? In the U.S. alone, multiple pilot programs3 have been implemented, and the results are encouraging, particularly in terms of mental health and access to healthcare. With a basic income, artists can take better care of themselves and are more likely to stay committed to their practice over the long haul, even after starting families.

Owning A Piece Of An Artist’s Future

Today, I came across a model4 that takes a very different approach from universal basic income. Instead of supporting all artists equally, it focuses on investing in the most promising ones early on—with the hope of future returns. It’s kind of like how people invest in tech startups or real estate: if the value goes up, investors can sell their shares for a profit. In this case, the “shares” are fractional ownership in an artist’s future success. These shares can be held by collectors, patrons, gallerists, supporters—and even the artists themselves—giving everyone a stake in the potential value of the work if it takes off.

Just as artist-run spaces, co-ops, and mutual aid networks reflect grassroots economic alternatives, fractional equity and art funds offer structural tools that can scale those values into broader markets.

In the traditional art market, an artist gets paid once—when the work is sold. But in a fractional equity model, the artist keeps a share of the artwork’s future value. That means if the piece is resold or generates income later, both the artist and anyone who holds fractional shares benefit. This is a big shift. Musicians and authors already earn royalties whenever their work is played or sold, but visual artists—like painters or designers—typically don’t.

What if artists were treated more like co-investors in their own creations? Instead of being cut off after the first sale, they’d retain a stake in the ongoing value of their work. It’s similar to how software engineers might receive both a salary and stock options in a startup. The same could apply to artists and creative entrepreneurs—giving them the financial runway to take bigger creative risks and focus more seriously on their practice, knowing there’s long-term potential in what they’re building.

A study conducted by Amy Whitaker from the Visual Arts Administration at New York University and Roman Kräussl, Luxembourg School of Finance, University of Luxembourg, found that even though only about 11% of the artworks in the study were resold, the returns—or how much money was made—were still better than investing in the U.S. stock market during the same time.

Market Driven Patronage

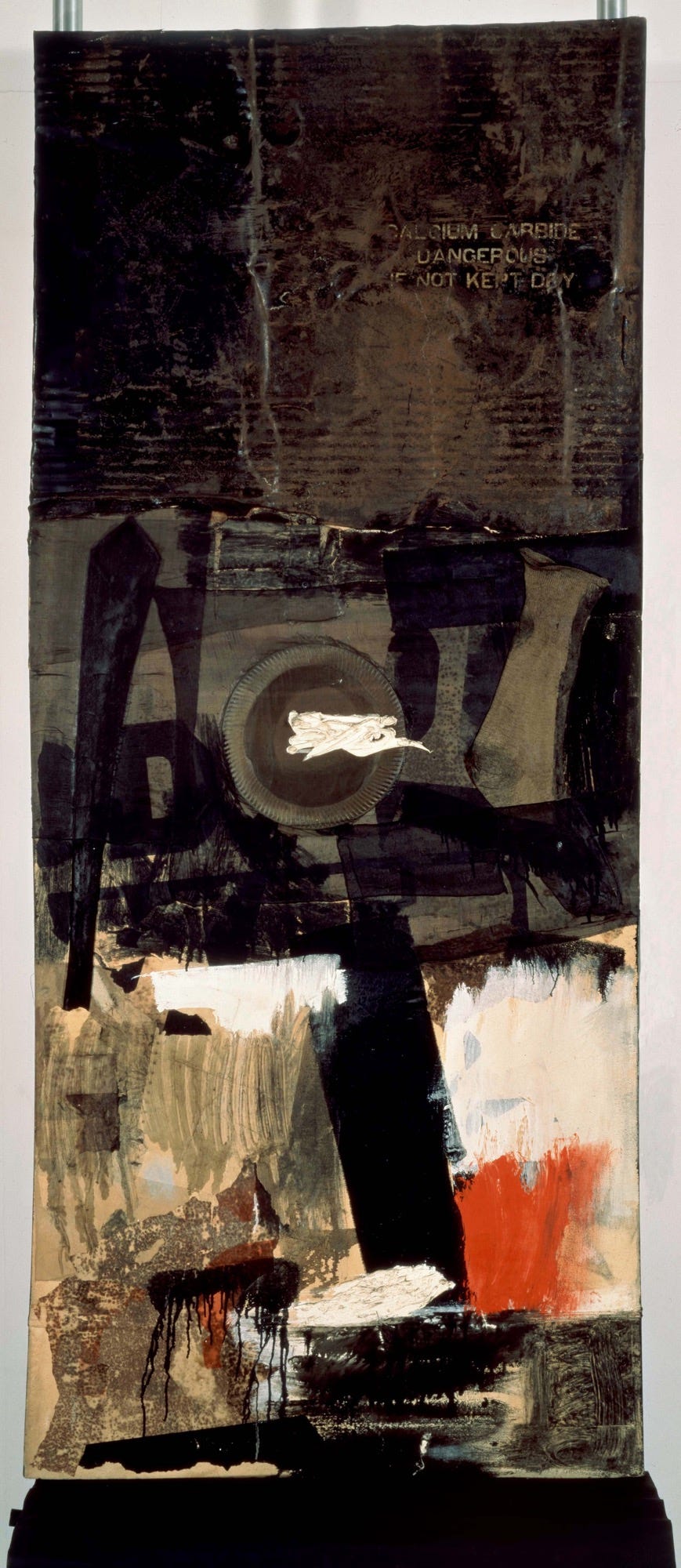

This highlights the undervalued nature of early creative work. The artists and dealers take risks, which generates value that they do not monetize on. The amount of money an artwork earns over time can vary significantly, depending on when it is measured. For example, Robert Rauschenberg’s painting Forge was first sold in 1959 for $1,000. It sold again in 1973 for about $60,000, and then in 2007 for $6.2 million.

When Rauschenberg first sold his paintings, he wasn’t famous yet—nor were his early gallerists, Betty Parsons and Richard Bellamy, who also took chances on artists like Pollock and Rothko. They were making bold bets, and some of those bets paid off in a big way. Like with tech startups, it’s nearly impossible to predict who will make it, but having equity in an artist’s career can lead to major returns—for the artist and for the collectors and gallerists who believed in them early on.

Rauschenberg might seem like an exceptional case now, but the study I read showed that the biggest profits came from those earliest investments, when no one knew who he was. He had been working on it for years before it sold. Dealers like Richard Bellamy took real financial risks, even giving artists advances to keep them going. Another major figure, Leo Castelli, famously offered monthly stipends to his artists so they could focus on their work. That early support laid the foundation for careers—and markets—that would eventually skyrocket.

Without these early bets—by the artists, the dealers, and the collectors—much of this now-celebrated work might never have existed.

Artists and their early supporters should have access to equity and ownership structures, just like start-up founders and early employees do in other industries. Of course, there are risks in treating art as an asset—especially if it prioritizes market trends over creative integrity…

This also creates major opportunities like market-driven patronage, where supporters can invest early in artists and not just buy their work as consumers. And diversified art funds, where investors can spread risk across shares of multiple artworks and artists like a stock portfolio.

At its core, this model reframes creative labor not as a one-time product for consumption but as a long-term investment, with the potential for returns shared more equitably between artists and backers.

Of course, not every artist will benefit directly from holding equity in their own work—but they can still participate by buying shares in another artist’s early-stage pieces. It’s a way to support fellow artists while also spreading financial risk. After all, someone working alongside you in a shared studio could turn out to be the next Frida Kahlo or Rothko. Having a stake in their success not only helps them grow but could also benefit you as one of their early supporters.

Conclusion

As the art world grapples with deep inequalities and unstable income structures, it’s clear that no single solution—whether direct subsidies, universal income, or market-based models—can address all the challenges artists face. Instead, a hybrid approach that combines public support with innovative financial mechanisms like fractional equity offers a more equitable and sustainable future.

By recognizing artists not just as producers of objects but as long-term value creators—worthy of investment, partnership, and shared ownership—we can begin to shift the culture around creative labor.

Supporting artists should not be framed as charity, but as an investment in cultural infrastructure with returns that are social, emotional, and, yes, financial. The question now is not whether we can afford to support artists differently, but whether we can afford not to.

Great article and I fully agree with this concept - artists and early supporters should have a stake in artworks.