A liberal artist who painted like a conservative

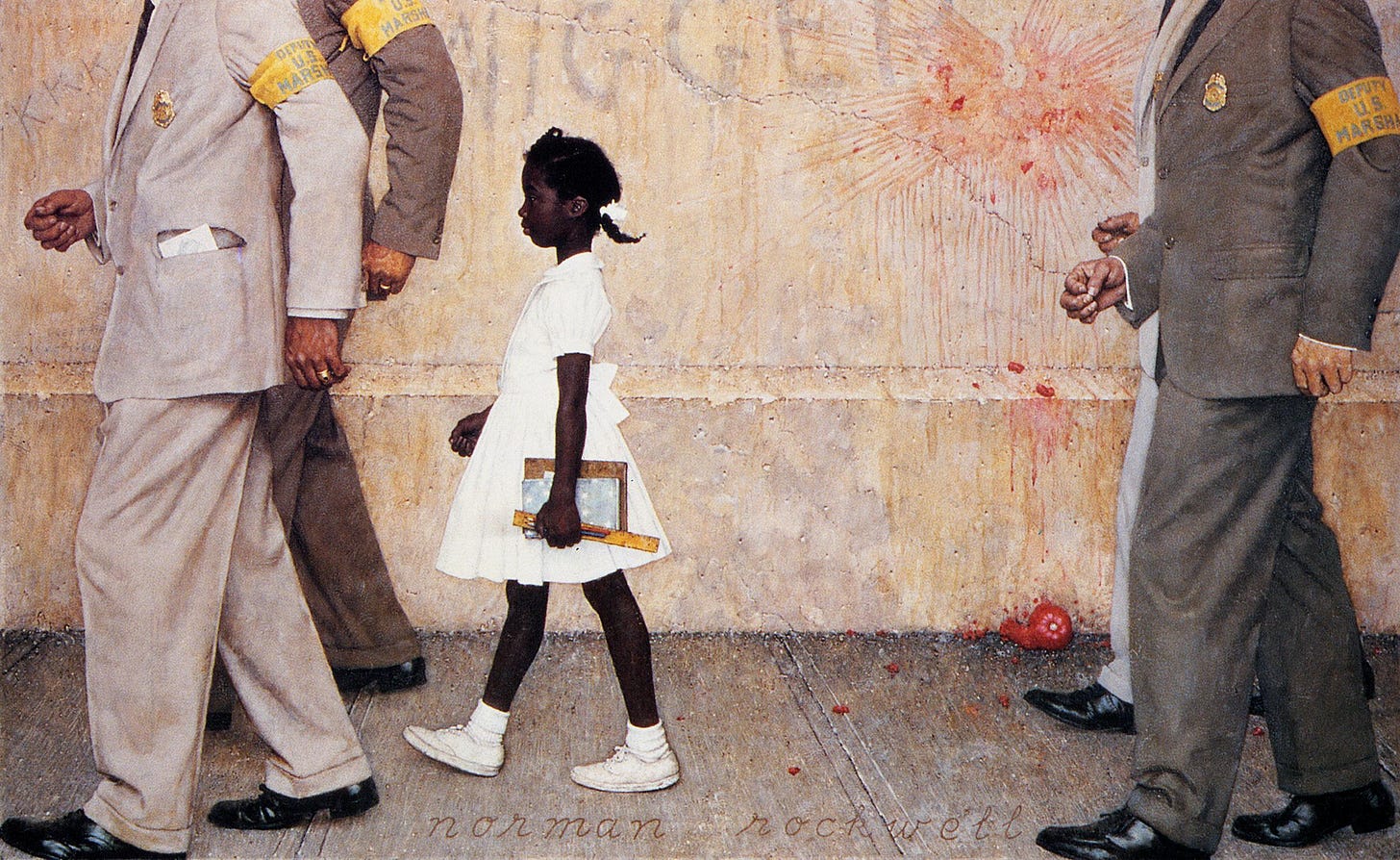

For 50 odd years of his life, Norman Rockwell drew vignettes of white families doing everyday things in small town America. They are technically brilliant, feel good illustrations that cater to people who would vote for Donald Trump today. His work had broad popular appeal in an era where most of publishing was done by white people for other white people. Rockwell was financially successful and popular. From his paintings one could safely put him in the conservative bracket because one of his main illustration clients was the Saturday Evening Post which was a conservative publication and restrictive of what Rockwell could draw.

However Rockwell was liberal, albeit a scared one. He worked at the Evening Post for 50 years and it was hard to separate his identity from the magazines. His liberal side finally broke through in the 1960’s when he painted ‘The Problem We All Live With’ depicting Ruby Bridges, the first black child attending a white elementary school in the South. By this time he had parted ways with the Evening Post and was working with Look Magazine that gave Rockwell the opportunity to pursue subject matter that interested him. 1

A conservative artist who painted like a liberal

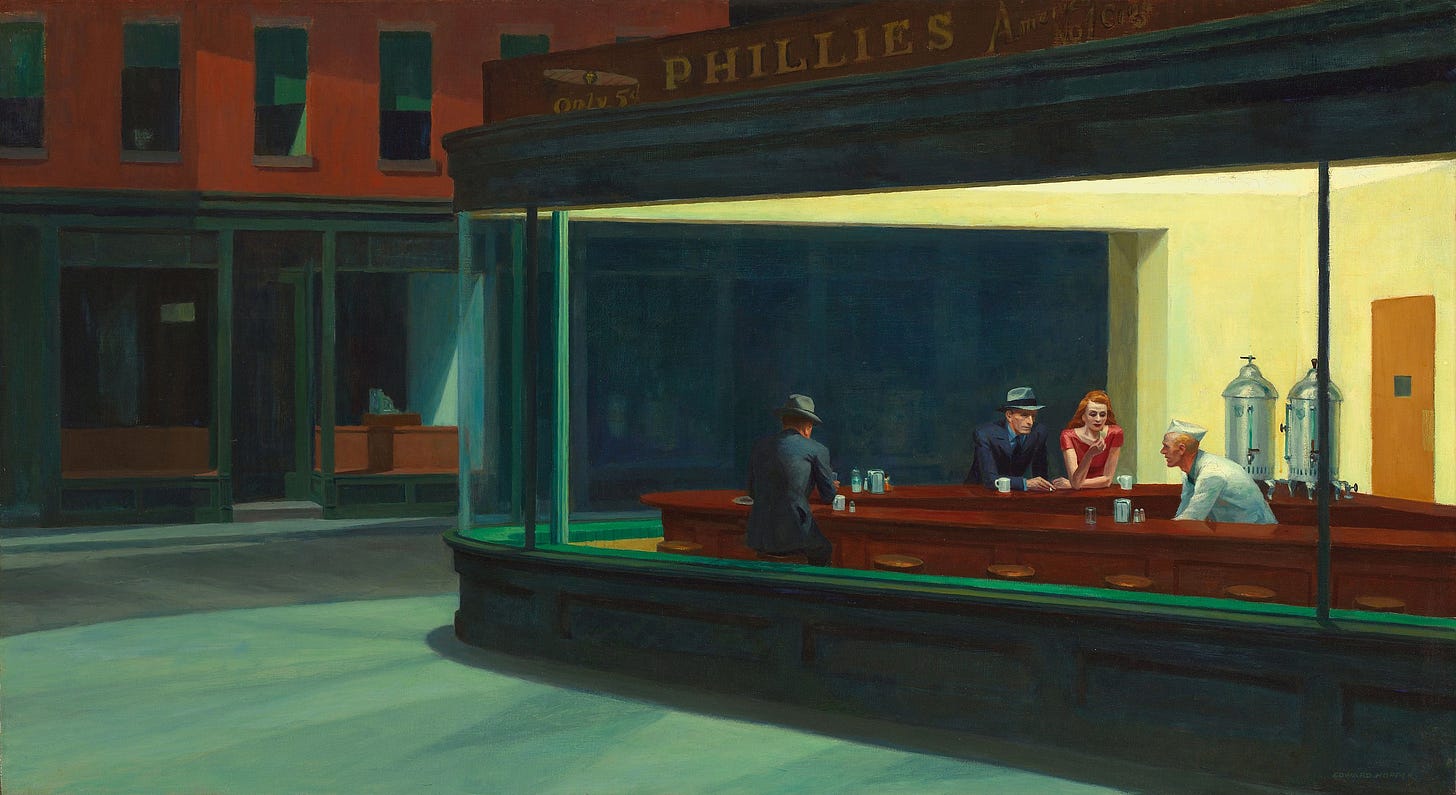

Edward Hopper on the hand was a political conservative. He wasn’t a fan of the New Deal art programs, which he thought promoted mediocre art, and he voted against Franklin Roosevelt (this detail is unclear). Did his political bent affect the way he painted? It is hard to say. His work has a strong individualist streak and he did not like being grouped with other artists or with art movements. But that barely passes the political litmus test.

Here is what Clement Greenberg, the leading proponent of Abstract art who was instrumental in making Pollock a celebrity, wrote about Hopper in 19462.

"Hopper is not a painter in the full sense; his means are second-hand, shabby, and impersonal….But if he were a better painter, he would, most likely, not be so superior an artist."

Greenberg thought of Hopper as a superior artist but a poor painter. This quality of ordinariness, suffused with the aura of awkward people as if in a Hitchcock drama, appealed to him and subsequently to other liberal art critics. His art went from being ‘provincial’ to being an icon of symbolism in Europe and America.

Conservatism is often conflated with realism and nostalgia for what was good and has been lost (think MAGA). Hopper’s art does not fall into that category. It is brooding, dark, lonely, and not welcoming or pretty, as some of Rockwell paintings. In spite of his subsequent popularity with liberal critics, Hopper’s identity was deeply rooted in nationalism and him being an Anglo-Saxon artist.

Aesthetic preferences and response to uncertainty

Donnagal Young is the author of ‘Wrong, How Media, Politics and Identity Drive our Appetite for Misinformation’. According to her, how we tolerate uncertainty or the gray areas in our lives, informs how we view the world and vice versa. This could be everything from our career choices to our preferences in art and literature and our politics. People who have a higher disposition for monitoring threats in their environments will not have a high tolerance for ambiguity, they need certainty and predictability3.

This extends to the research on the psychology of aesthetic preferences and can help predict whether a person will enjoy abstract art or realistic art. Understandably, people with high tolerance for ambiguity like abstract art, movies with open ended endings, and jazz. These type of people also tend to be more open to issues like gender fluidity, or understanding why someone committed a criminal act, versus if they should be given a death penalty for it. As you may have guessed, these people tend to be liberal.

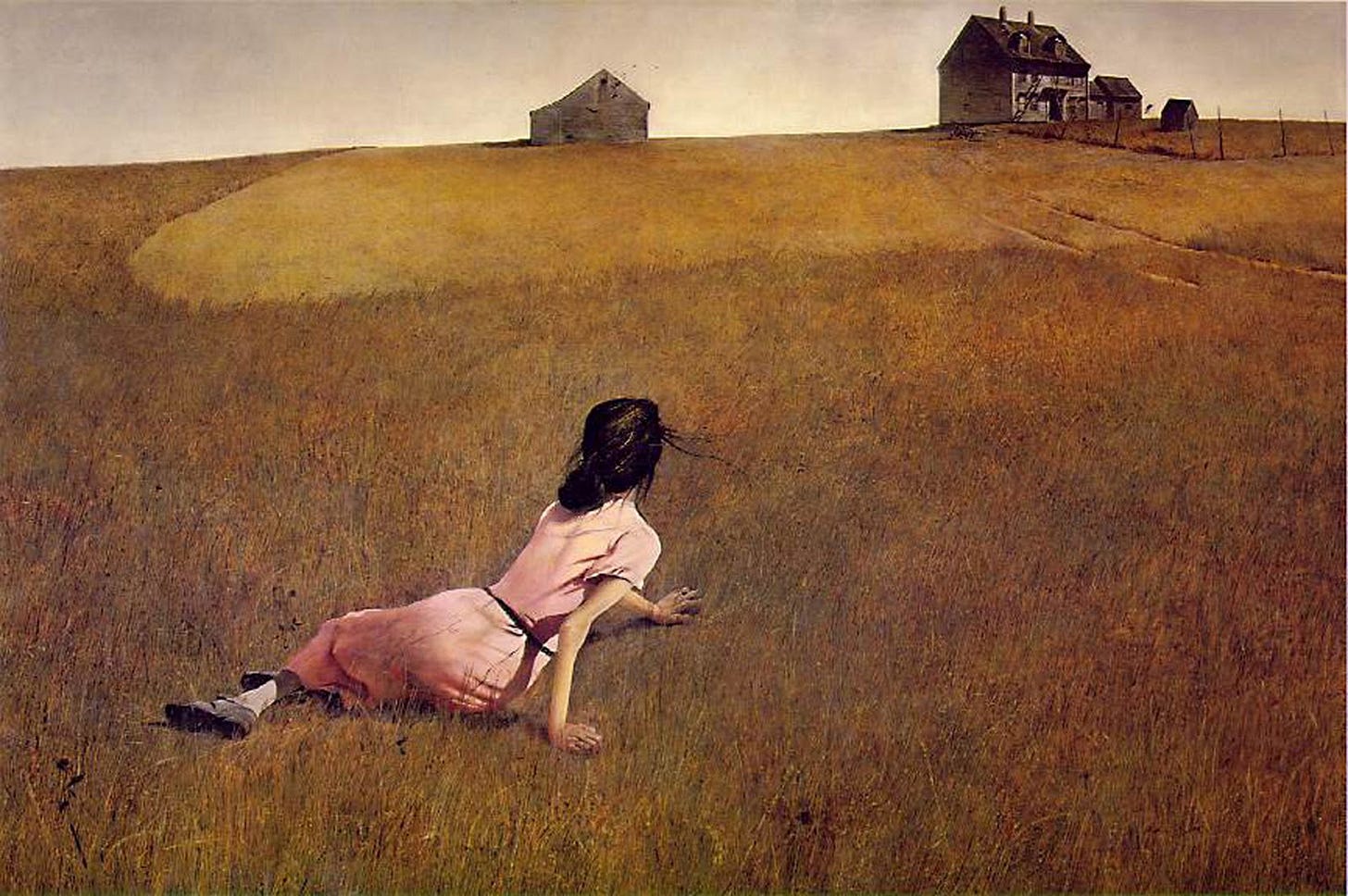

Realism and regionalism have been squarely in the conservative art space because of its familiarity and unambiguity. Andrew Wyeth is at the forefront of this type of art. His work stands in stark contrast with the abstractionists of that time. Like Rockwell, he was highly technical and skilled, but reviled by most critics for a large part of his career. His obituary in NY times duly notes that he voted for Nixon and Reagan. Here is what the dean of the Yale School of Art and Design said about Wyeth’s work in an article published in NY times after Wyeth died4.

“Wyeth was an anti-modern painter,” Mr. Storr said. “He did paintings that never changed, in a style that never changed. His image is one of stasis in a world that changed dramatically around him, and for my money that is a conservative position. It is in many ways a futile exercise, but he did it with great energy and conviction.”

We have come a full circle

Abstraction was a response to social and cultural change in its hey day. It is just about a hundred years old with Mondrian, Kandinsky, Malevich, leading the way5. Mondrian’s work started as representational and evolved to abstraction as a way to express his philosophical beliefs. His art became more inward looking. This is a true of a lot of artists who viewed art as a way of expressing themselves versus recording an event. Photography and film were were becoming popular, and artists felt relief from being thought of as craftspeople or illustrators, even though a lot of artists including Rockwell and Hopper supported themselves as illustrators for magazines.

Here are a couple of great quotes from the Artnet podcast, the Art Angle, that encompasses everything about abstract art and expressionism.

“It is better to capture the glorious spirit of the sea, than to paint all of its tiny ripples.”

“Abstract expressionists were after emotions, visceral feeling of paint on canvas rather than the figurative interpretation of imagery and painting”.

Today modern and abstract art is not considered revolutionary but is still wildly popular. It has become a reasonable style of self expression for artists, where artists do not have to worry too much about skill and technique.

Jerry Saltz, acclaimed art critic surmises that one could love a certain art period, and love drawing portraits, but the end result needs to say something about the thoughts and feelings of the artist. He also talks about the need for radical vulnerability in art. Could abstract art exist if it wasn’t for artists wanting to break away from the norm? The answer is no, art takes courage, but also a certain kind of vulnerability.

This applies to artists on both sides of the political aisle. Here is a great quote from a source I cannot find unfortunately:

“Conservative buyers of art may lean to traditional forms; artists may choose to cater to that taste. But to believe that conservative art reaches its apex when it is indistinguishable from a photograph is to shut out vast opportunities for artistic expression and appreciation.”

Hoppers art is a great example of this. It challenged societal norms of effusive nostalgia, and infused symbolic layers into his art, all while remaining within the framework of realism.

Art represents the spirit of the age, the technological, political and spiritual advances or lack thereof. It also represents, the inner world and turmoil of the artist. How it is conveyed is up to the artist, how it is received it up to the critic, collector and the public. If both align, an artist may see success, if not, they may see it as a building block to their next project, or be satisfied in the feeling that they put their most authentic self out there. However if the artist is not doing any of the above, they have work to do, irrespective of their political affiliation.

https://www.commentary.org/articles/terry-teachout/outing-norman-rockwell/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/hopper-156346356/

https://hiddenbrain.org/podcast/sitting-with-uncertainty/

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/17/arts/design/17deba.html

https://news.artnet.com/multimedia/the-enduring-obsession-with-abstraction-2429801