What it took to be the first woman artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale

Jenny Holzer's journey from Gallipolis, Ohio, to the most sought-after international art exhibitions in the world

I published this article exactly a year ago and am pulling it from the archives so that more of you can read about Jenny Holzer’s artistic journey. She is one of my favorite artists and an inspiration.

Jenny Holzer grew up in a working-class family in Ohio and had a somewhat unconventional academic journey, changing schools annually in the later years. She attended two high schools, then went to Duke University, the University of Chicago, Ohio University, and eventually the Rhode Island School of Design. Her approach to art in the early years was experimental, a stance that clashed with the conservative painting department at RISD. Fortunately, she was accepted and then succeeded in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, which paved the way for her signature text-based art.

There are many reasons why Holzer’s career took off in the way it did. Unlike Mauricio Cattelan, whose art connections result from his exuberant personality and charm, Holzer is reserved and thoughtful. However, her art is populist, political, and public. She critiques consumerist culture by using propaganda tools against it.

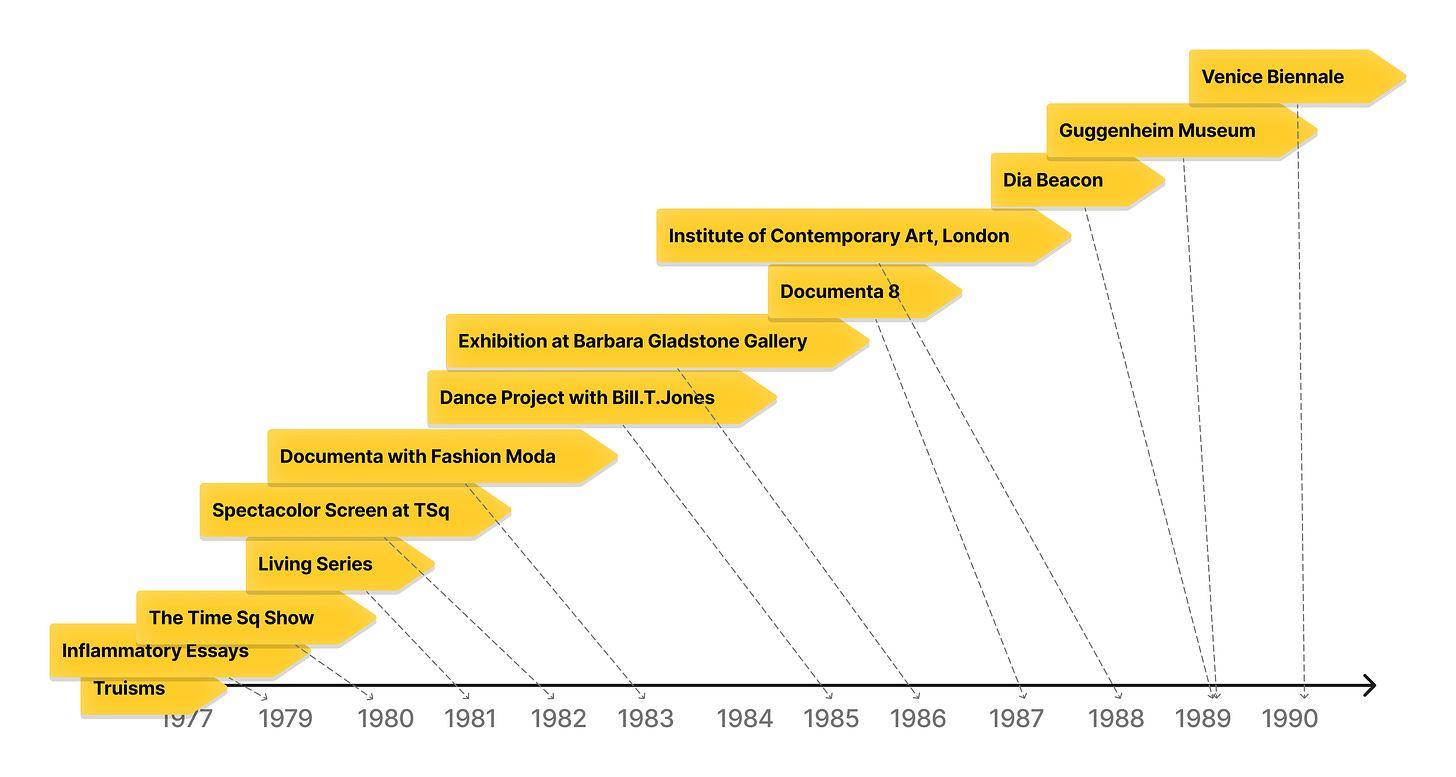

This article will focus exclusively on the initial ten years of Jenny Holzer's art career, spanning from her early ventures into text-based posters, known as Truisms (1977-1979), to her groundbreaking achievement as the first female artist chosen to represent America at the Venice Biennale in 1990.

1. Street posters as the Instagram of the past

At the Whitney, Holzer made a shift from painting to content creation. Being an avid reader, she dedicated time in the library, immersing herself in literature about politicians, visionaries, and left-wing thinkers. Captivated by the succinct nature of captions and their ability to simplify complex images and diagrams, she began distilling her extensive reading into concise one-liners, naming them 'Truisms.' These nuggets of accessible information were then displayed on the streets as posters, essentially condensing critical insights from her reading list at the Whitney into bite-sized pieces.

These iconic street posters attracted the attention of critics and curators in the New York art world. They were noticed by the famous artist Dan Graham, who was known for his architectural art installations, especially those that used glass and mirrors. These posters functioned as present-day Instagram feeds. Graham mentioned Holzer's artwork to Manifesta’s chief curator, Kasper Koenig1, and Holzer got to show her work at Westkunst in Germany right after. This was the beginning of her long art career.

2. An early form of Content Marketing

Even though Holzer herself can be categorized as introverted, she thought of her art practice as standing on a soapbox2. She kept her ‘Truisms’ short and understandable to reach a big audience. In a way, she invented an early form of content marketing. In the future, she will utilize LED billboards as a way to communicate her content. This leaning towards mass media did exactly what she set out to do: get many people to see her work. In an interview with the New York Times, she says :

''My legacy from growing up in the 60's is that I want to make art that's understandable, has some relevance and importance to almost anyone. And once I've made the stuff, the idea is get it out to the people. I want them to encounter it in different ways, find it on the street, in electric signs and so forth. I like fooling with different presentations and modes. I like to make it turn purple and go upside down.''

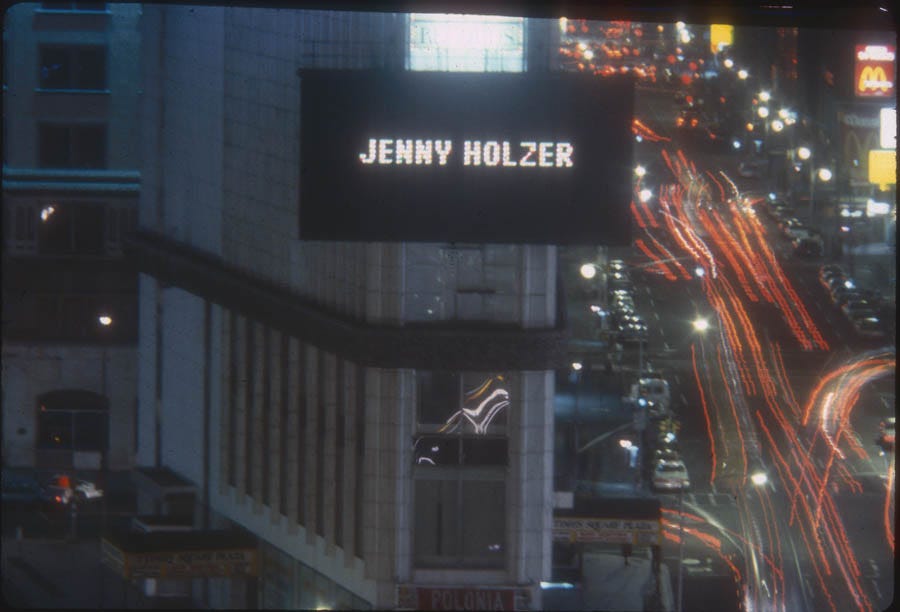

In 1982, Holzer participated in the inaugural public art fund media-based project Messages to the Public. The project aimed to remove art from galleries and place it in the city streets. Holzer’s work perfectly fits this mission statement. The show featured a series of artist projects created specifically for the Spectacolor light board, which was installed at a prominent location in Times Square at the time.

Here is an excerpt by Mike Glier, Holzer’s husband, from a short video around her installation for the Venice Biennale:

“I find Jenny’s solution very successful in that she has co-opted, this media look by using electronic signs and has used all the glitz and attractiveness and the sense that it is a future material, a technology that can take an interesting place in the future, but her subject matter has been very personal, she writes about what she thinks the world should be, in no uncertain terms. So it is a personal voice in the public form.”

3. User testing

Software designers use user testing to test their software with users. This allows them to get feedback on their designs and iteratively improve them so that users find them easier to use.

Holzer was doing something similar with her public art. In the early years, she would leave breadcrumbs in the shape of letters outside for the birds to eat. She always looked for people to find something interesting to engage with or puzzle over. She would then go back to see if anybody had noticed what she had created. This helped her hone in on what attracted attention and what didn't.

4. Inter-connectedness

In one of my previous articles, I discussed the role of social structures in the success of artists. The study3 suggests that success and fame are not just about being creative but about who you know and how diverse your connections are. When Holzer arrived in Manhattan in 1978, she found her artistic home in feminist art collectives and other artist-run populist collectives.

In her essay, Lucy Lippard, an American art critic, activist, and curator, looks back at 30 years of feminism in the art world and says:4

“..in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, a range of young artists’ collectives revamped public art, often with a feminist twist, as a new generation of major women artists—among them Jenny Holzer and Kiki Smith—arrived on the scene within new young mixed-gender collectives and a retro-punk art scene.”

Holzer was included in Lippard’s exhibition called ‘Social Strategies by Women Artists’ alongside other feminist artists of the time in 1980.

Holzer moved her street art ‘Truisms’ from the street to alternative community-driven art spaces like Franklin Furnace in downtown Manhattan and Fashion Moda in the South Bronx. Holzer was a part of a New York City avant-garde artist group called Collaborative Projects Inc. or Colab (1979-89), which was formed as a collective in 1977. Fashion Moda (1978-93) and Colab produced a large open exhibition called the ‘Times Square Show’ in 1980, set up in an abandoned massage parlor in Manhattan Times Square. Holzer was a part of this exhibition.

In 1982, Stefan Eins, the founder of Fashion Moda, and Holzer organized one of Fashion Moda’s most important projects: three temporary stores at Documenta, a prestigious modern and contemporary art exhibition held in Kassel, Germany. The exhibition attracted considerable notoriety for its populist theme.

The Fashion Moda stores at Documenta functioned as a way for artists to distribute their work to a broader audience and critique large events that were closely tied to the traditional art market. The store sold items like T-shirts and jewelry and found objects that were intentionally inexpensive to make them affordable to many. Many other artists, including Eins and Holzer, who had participated in the Times Square show, sold pieces at the Fashion Moda stores at Documenta. Holzer’s truisms were displayed in German at the main exhibition. In the Fashion Moda store, one could purchase a T-shirt with one of her truisms printed on it. Holzer marketed herself by reproducing her iconic phrases as a souvenir of the original piece, which was quite successful.

5. Topicality and the International Circuit

Like the on-trend ultra-contemporary artists of color today, Holzer was coming of age at a time when there was widespread interest in site-specific, socially concerned art. According to an article in the New York Times in 1988, Holzer was chosen to represent America at the Venice Biennale in 1989 because the advisory committee sought someone particularly American who was doing socially concerned art. Here is an excerpt from the New York Times:5

Holzer was chosen in part because the advisory committee was looking for an artist who was particularly American. With her inclusiveness and her vernacular materials and language, Holzer embodies an American ideal of democracy. It is the combination of experimental form and traditional American content, and the way they are fused together, that makes her less a controversial than a logical choice at this time.

Given her type of work, Holzer was invited to a few international exhibitions in the 1980s. Places like Documenta in Germany and Munster in France focused on socially oriented and site-specific art. Her art aligned with that of some of the top international exhibitions of the time, helping her prove herself internationally. This eventually led to her being in the running for the Venice Biennale, which she won.

6. Relevance and Consistency

Holzer’s work has always responded to what’s happening in the world. Here is an excerpt from an article for Artspace :

“This balance between the momentary and the monumental continued throughout Holzer’s career…., Holzer has always responded to the tenor of the times.

Her Laments series (1988-89) was made during the AIDS epidemic; her War series (1992) responded to the first Gulf War. Lustmord (1993-94) meanwhile, was, in part, prompted by the conflict in Bosnia; while her more recent Redaction Paintings (2008), works based on declassified and partially redacted documents, was made partly in response to the war on terror.”

Holzer’s work depicts the voices of ordinary men and women around the country. It is democratic and aligned with a certain type of American curator. It strikes the right balance between activism and art, and it is timeless because it discusses present-day injustices. It never ages.

Holzer has consistently created text-based art. Her varied mediums have included billboards, projections, posters, painted signs, photographs, bronze plaques, and stone benches, among other things. This means she has stuck to presenting her ideas as words for almost 50 years even though she is no longer the author of her texts and finally returned to painting at age 70.

In Conclusion

Artists can glean essential insights from Jenny Holzer's early career.

Holzer's journey underscores the importance of embracing experimentation, urging artists to be open to novel approaches and styles. Innovating in presentation is key, as demonstrated by Holzer's use of unconventional platforms like street posters and LED billboards.

Understanding audience engagement is paramount. Effectively refining artistic strategies requires seeking feedback and adapting to preferences. Building connections within the art community, participating in exhibitions, and joining collectives mirror Holzer's path to success.

Staying relevant by aligning art with current events and societal themes is crucial, emphasizing the need to infuse work with contemporary resonance.

Diversifying artistic mediums allows for exploration and finding the most impactful ways to convey messages.

Seeking international opportunities broadens reach, exemplified by Holzer's success in global exhibitions.

Finally, adapting to changing artistic landscapes while being consistent and authentic ensures a meaningful and enduring career.

After seeing Barbara Kruger's Pledge, Will, Vow in Dallas last year I became really interested in the history around this group of artists/art movement. Really enjoyed the article and the pointers at the end.

Thank you! Both Kruger and Holzer are such powerhouses.